Photo © Djo Djokkos

Top predators are returning to France. At the start of the 1990s, there were five brown bears and a handful of Eurasian lynxes in the country. No wolves. All three species have made spectacular – but contested – comebacks.

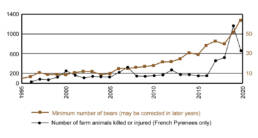

Although there were around two hundred brown bears in the Pyrenees a century ago, by 1990 the relict population of five was limited to the western end of the range, in the Béarn. Since then, there have been five campaigns of reinforcement: three bears in 1996/7, five in 2006, one (in Catalonia) in 2016 and two in 2018. By 2020, the population had grown to at least 64, following 16 births in that year.

Goiat was released in Catalonia (Spain) in 2016

Before the first bears arrived from Slovenia, the locals were consulted. Some clapped their hands, like André Rigoni, the mayor of the village where the first bear would be released. Others put their hands over their eyes. Fine, as long as it won’t affect me. Jean Lassalle, President of the Pyrenees National Park was one of those. And some clenched their hands into fists, like Augustin Bonrepaux, a local MP.

Over the years, the anti-bear movement has been growing in power in tandem with the bear population. It has captured the hearts of many local politicians. In 2019, over a hundred mayors organized a demonstration in Toulouse against bears.

In 2020, three bears were deliberately killed in the Pyrenees.

The reason? Dead sheep. The number of deaths is disputed. Shepherds complain that not all deaths are counted; conservationists say too many doubtful cases are included in the statistics.

There are contrasting views on the arrival of the bears. One shepherdess writes: “It was 1 June 2007 when we first saw evidence of a bear at Centraus [our farm]. It was one of those special little pleasures of life… That day, [my sons] Miguel, Manuel and Mario are watching the flock at Bouychet. Miguel, the oldest leaves his brothers and comes back to the sheep shed across the fields. When he arrives at the sheep shed, he explains to my husband and me that he has seen bear footprints. We don’t believe him, all the time we had been waiting.”

Catherine Brunet 2017 La Bergère et l’Ours, Vox Scriba (Tarascon-sur-Ariège), p 133.

That’s one view, but not typical. Many farmers are completely against the return of bears. Gisèle Gouazé is one of them. She talked to me after losing 209 sheep in a single attack, criticising the government for exhorting farmers to improve animal welfare while at the same time releasing bears that massacre them. “Animal welfare in the mountain pastures,” she complained, “I ask myself what that means now.”